|

|

@@ -0,0 +1,109 @@ |

|

|

|

|

|

* Exercise 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Safety wheels are now officially off. |

|

|

|

|

|

To verify this, set nopPadded to false in Manifest.scala and observe as all hell |

|

|

|

|

|

breaks loose. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Let's break down what's going wrong and what we can do about it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

** RAW Hazards |

|

|

|

|

|

Consider the following program: |

|

|

|

|

|

#+begin_src asm |

|

|

|

|

|

main: |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x2 |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x1 |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x2 |

|

|

|

|

|

#+end_src |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In your implementation this will give you wrong results since the results |

|

|

|

|

|

of the first add operation will not be available in the registers before |

|

|

|

|

|

x1 is fetched for the second and third operation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Your first task should therefore be to implement a forwarding unit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

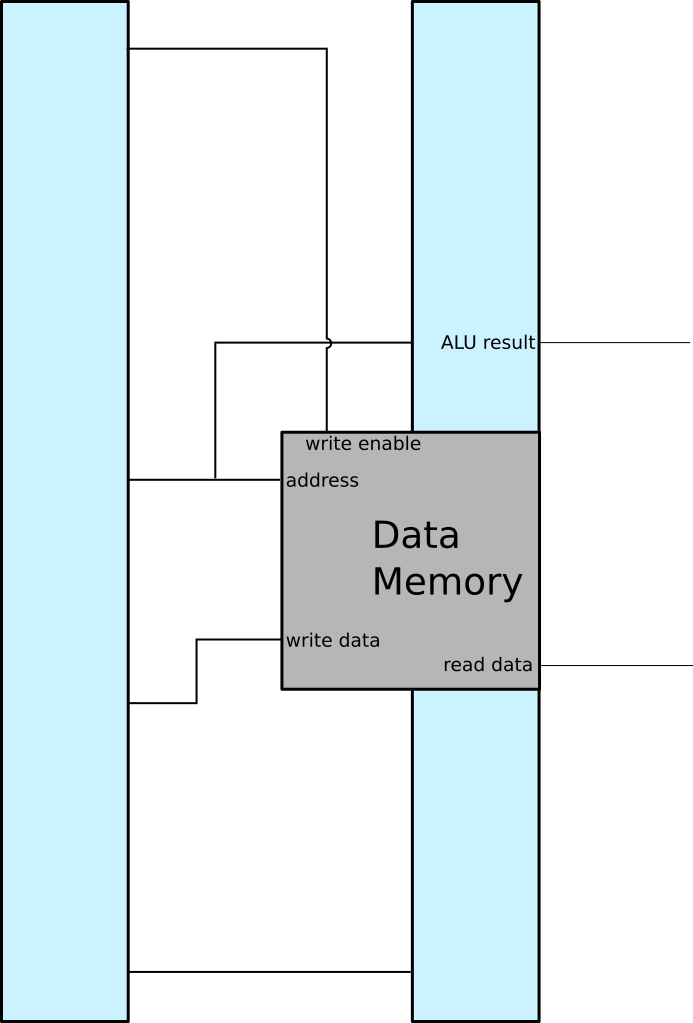

The forwarding unit is located in the EX stage and is responsible for selecting |

|

|

|

|

|

the ALU input from three possible sources. |

|

|

|

|

|

These sources are: |

|

|

|

|

|

+ The value received from the register bank |

|

|

|

|

|

+ The ALU result currently in MEM |

|

|

|

|

|

+ The writeback result |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The forwarder prioritizes as follows: |

|

|

|

|

|

+ If the input register address is not the destination in either MEM or WB, select the |

|

|

|

|

|

register. |

|

|

|

|

|

+ If the input register address is the destination register in WB, but not in MEM, select |

|

|

|

|

|

the writeback signal. |

|

|

|

|

|

+ If the input register address is the destination register for the operation currently |

|

|

|

|

|

in MEM, select that operation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is a special case you need take into account, namely load operations. |

|

|

|

|

|

Considering the following program: |

|

|

|

|

|

#+begin_src asm |

|

|

|

|

|

main: |

|

|

|

|

|

lw x1, 0(x2) |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x1 |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x1 |

|

|

|

|

|

#+end_src |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When the second operation (~add x1, x1, x1~) is in EX, the third clause in the forwarder |

|

|

|

|

|

is triggered, however the result is not yet ready since fetching memory costs a cycle. |

|

|

|

|

|

In order to fix this the forwarder must issue a signal that freezes the pipeline. |

|

|

|

|

|

This is done by issuing a signal to the barrier registers, telling them to _not_ update |

|

|

|

|

|

their contents, essentially repeating the last instruction. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There are many subtleties to consider here. |

|

|

|

|

|

For instance: What should happen to the instruction currently |

|

|

|

|

|

in MEM? If it too is repeated the hazard detector will trigger next cycle, effectively |

|

|

|

|

|

deadlocking your processor. |

|

|

|

|

|

What about when the write address and read address are similar in the ID stage? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Designing a forwarder can take very long, or it can be done very quickly, all depending |

|

|

|

|

|

on how *methodical* you are. My advice is to design the algorithm first, then when you're |

|

|

|

|

|

satisfied implement it on hardware. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

** Control hazards |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider the following code |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

#+begin_src asm |

|

|

|

|

|

main: |

|

|

|

|

|

beq zero, zero, target |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x1 |

|

|

|

|

|

add x1, x1, x1 |

|

|

|

|

|

j main |

|

|

|

|

|

target: |

|

|

|

|

|

sub x1, x2, x2 |

|

|

|

|

|

sub x2, x2, x2 |

|

|

|

|

|

#+end_src |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Depending on your design the two add instructions will be fetched before the beq jump happens. |

|

|

|

|

|

Whenever a branch happens it is necessary to flush the spurious instructions that were fetched |

|

|

|

|

|

before the branch was noticed. |

|

|

|

|

|

However, simply waiting until the branch has been decided is not acceptable since that guarantees |

|

|

|

|

|

lost cycles. |

|

|

|

|

|

In your first iteration, simply assume branches will not be taken, and if they are taken issue |

|

|

|

|

|

a warning to the barriers that hold spurious instructions telling them to render them impotent |

|

|

|

|

|

by setting the control signals to do nothing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* Putting the pedal to the metal |

|

|

|

|

|

Once you have a design that RAW and control hazards you're ready to up the ante and add some |

|

|

|

|

|

improvements to your design. |

|

|

|

|

|

Some suggestions: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

** Branch predictor |

|

|

|

|

|

Instead of assuming branch not taken, use a branch predictor. There are many different schemes, |

|

|

|

|

|

but I advice you to stick to a simple one, such as 1-bit or 2-bit. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

** Fast branch handling |

|

|

|

|

|

Certaing branches like BEQ and BNE can be calculated very quickly, wheras size comparison branches |

|

|

|

|

|

(BGE, BLE and friends) take longer. It is therefore feasible to do these checks in the ID stage. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

** Adding a data cache |

|

|

|

|

|

Unless you have already done the two suggested improvements, do not attempt to create a cache. |

|

|

|

|

|

The first thing you need to do is to add a latency for memory fetching, if not you will have |

|

|

|

|

|

nothing to improve upon. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you still insist, start with the BTreeManyO3.s program and analyze the memory access pattern. |

|

|

|

|

|

What sort of eviction policy and cache size would you choose for this pattern? |

|

|

|

|

|

You should try writing additional benchmarking programs, it is important to have something measurable, |

|

|

|

|

|

and the current programs are not made to test cache performance!! |